Composing the score for “MechWarrior 4: Vengeance” was a true career milestone on many levels. At the time of the project’s inception, I was working as the staff composer for Chicago-based FASA Interactive, along with a stellar team of visual artists and computer programmers. When our company was acquired by Microsoft in 1999, we relocated to Redmond, Washington.

Set in the BattleTech universe, a concept created by FASA Interactive’s Jordan Weisman, the game revolved around a world where wars were fought by giant, human-piloted robots called Mechs. It was the fourth game in the MechWarrior series and was published by Microsoft in 2000.

Adding to the fun, my music for “MechWarrior 4: Vengeance” was released on a soundtrack CD by Varese Sarabande, a record label that is renowned for its catalog of motion picture soundtracks. It was quite an honor to be included in such a prestigious music catalog. As well, the game had a sophisticated storyline and the music was treated as an essential element in telling that story.

In my liner notes for the CD, I explained, “The music of MechWarrior 4: Vengeance is driven by the epic stories that encompass the BattleTech universe. Although it is science fiction that takes place 1,000 years in the future, it also embodies the human qualities that we see and feel in our lives today. It’s a time when honor, bravery and courage are valued and rewarded. It also reminds us that humans can be ruthless, treacherous and cowardly. All of these traits and emotions were integral to the score. And of course, the massive Mechs were also inspiration for more than a few of the cues.”

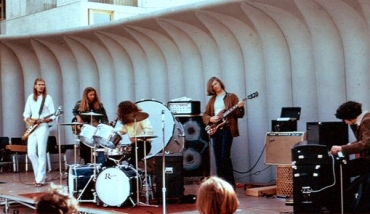

With Microsoft as the game’s publisher, I had the luxury of hiring outstanding live musicians (brass, woodwind and string players from the Northwest Sinfonia) and guitarist Clifford Allen Garrett to fill out my compositions, on which I played keyboards and percussion. Stan LePard (composer for “Crimson Skies”) assisted with orchestration and Simon James conducted.

More than a decade after the release of “MechWarrior 4: Vengeance,” I remain very proud of the game and the soundtrack.